Spirituality is the ego’s final disguise. While most people chase money, status, or pleasure, spiritual seekers chase something far more insidious: the identity of being above it all.

Humility is the hardest mask to remove.

Picture this: Eighteen-year-old me, backpacking through Southeast Asia with my high school friends, absolutely convinced I was on the verge of a profound awakening. 30 students from my high school were led by a tour guide named Vit to see the Buddhist temples, villages, night markets, and many other sights to behold.

A week into our Thailand sightseeing, we arrived in Cha-am, a beachside town overlooking the Gulf of Thailand. As our tour bus navigated the sea of honking cars and scooters, I scratched my chin in anxious contemplation.

“What an insane world” I said aloud, “everyone hurrying around toward their pointless desires…”

I was alluding to what I’d later learn was called, in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy, “Samsara,” the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth.

“What are you going to do then?” asked Jenny, a girl who’d already graduated from our school but still signed up for the trip. “Become a monk?”

She was cracking a joke, but it cracked my mind open. I silently gazed out upon the enormous ocean, feeling its weight.

The bus parked to let us out at our hotel, and I slowly shouldered my luggage while everyone else excitedly leaped outside to soak it all in.

While my friends were cracking jokes about elephant-headed Ganesha statues — embarrassing me terribly — and generally acting like the delinquent teenagers we were, I was busy being serious about my spiritual search.

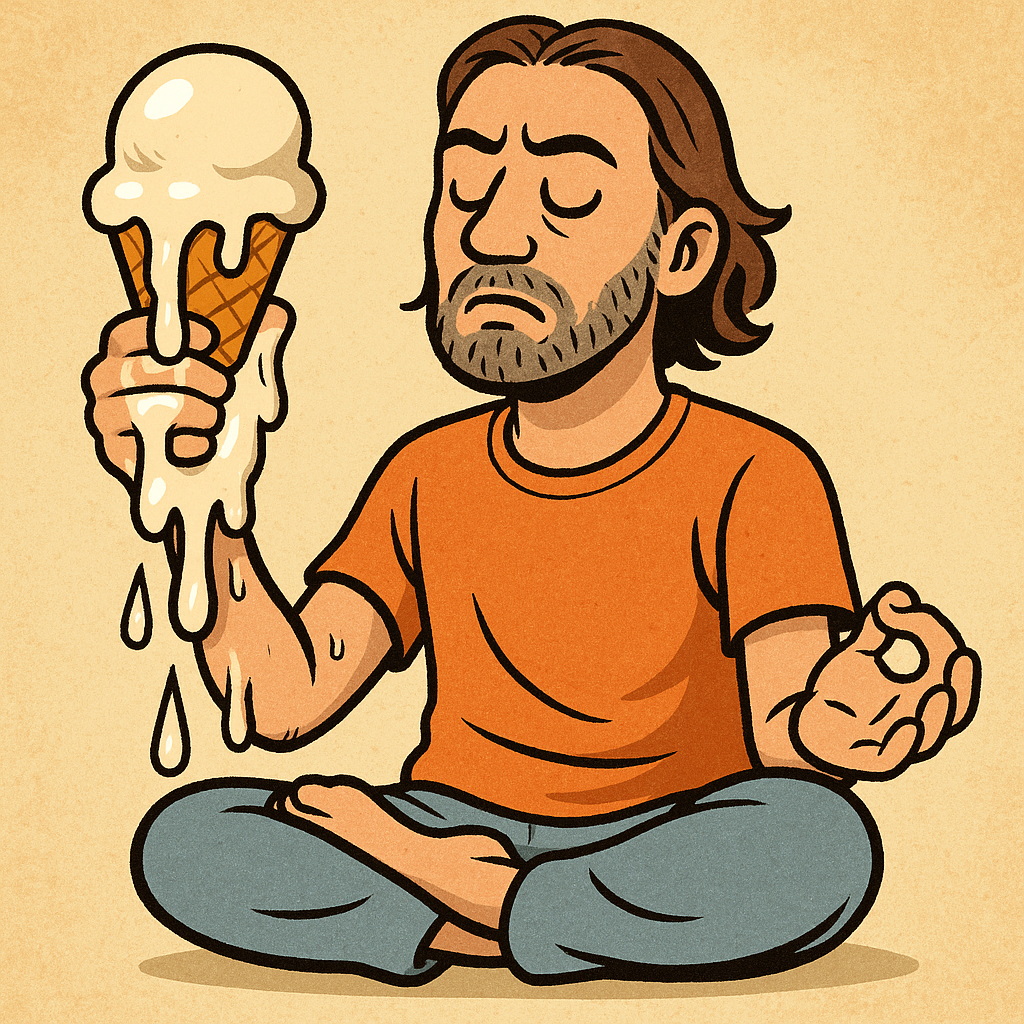

Right outside the hotel was an ice cream stand. My two best mates dove in immediately, present to the simple pleasure of cold sweetness in Thailand’s sweltering heat. But me? I was busy peppering Vit with questions about Buddhism, meditation, and the nature of suffering. He honoured my curiosity while he chomped at his own two-scoop waffle cone.

“You said you were a monk for some years. Why did you leave the monastic life?”

The man had actually been a monk. He’d done the whole thing: shaved head, robes, monastery, meditation, the works. Then he’d chosen to return to the world. Had he been duped by the temptations of desire?

Then Vit dropped the bomb that shattered my carefully constructed deep-seeker performance. “I learned what I was meant to learn there, how to live in the present moment and see what is true, and the untruth of my thoughts. Now I’m here, happy to have a wife and kids, and a chance to show people this amazing place.” He waved his hand, gesturing to the landscape around us.

“Now, it appears your friends are excited to go explore!”

Indeed, they were already at the scooter rental booth across the path, inquiring about the cost to hop on some wheels.

Vit extended a handful of napkins to me, and glanced down at my ice cream cone to guide my attention to the fact that it was melting all over my hand.

I was missing the point spectacularly. There I was, judging my friends for their “unspiritual” behaviour, while they were actually more present than I was, fully engaged with the experience rather than trying to transcend or escape from it.

As Alan Watts writes in Psychotherapy East and West: “The ways of liberation make it very clear that life is not going anywhere, because it is already there. In other words, it is playing, and those who do not play with it have simply missed the point.”

This is the essence of what some call spiritual bypassing: using supposedly higher consciousness as a way to avoid the messiness of actual living. It’s the ego’s most sophisticated trick, convincing us that detachment from our ambitions, emotions, and desires is somehow more enlightened than engaging with them fully.

The Hermit’s Delusion There’s a beautiful illustration of this trap in the 12th-century Japanese classic Hōjōki (“An Account of My Hut”). The author, Kamo no Chōmei, lived through devastating fires, earthquakes, famines, and political upheaval that destroyed much of the capital. Witnessing this impermanence, he retreated to a tiny ten-foot-square hut in the mountains, believing he had found wisdom in renunciation.

Seems reasonable. However, even after achieving his ideal of detachment, Chōmei notices something troubling about himself. He writes:

“One calm dawning, as I thought over the reasons for this weakness of mine, I told myself that I had fled the world to live in a mountain forest in order to discipline my mind and practice the Way. And yet, in spite of your monk’s appearance, your heart is stained with impurity.”

Even in his perfect solitude, the ego found ways to assert itself. His very pride in his detachment became a new form of attachment. He thought he had escaped the wheel of samsara, but he had simply found a more covert way to spin it.

Chōmei’s final realization is devastating. “It is a sin for me now to love my little hut, and my attachment to its solitude may also be a hindrance to salvation.”

Here’s the paradox that makes Hōjōki so profound: Chōmei’s “failure” to achieve perfect detachment finally did produce something worthwhile, and lasting. Centuries earlier, the 8th century poet Tu Fu says it perfectly in his poem about dreaming of his friend Li Po:

‘Poetry that will last a thousand generations / comes only as an unappreciated life is passed.’”

By fully engaging with his anguish about impermanence — by writing about it, crafting it into art — Chōmei created something that outlasted all the “permanent” structures he’d seen destroyed. His honest struggle with attachment and detachment became a masterpiece that has now guided seekers for eight centuries.

The hermit’s hut becomes just another mental prison when it’s built from spiritual bypassing rather than genuine understanding. But when used as a place to wrestle honestly with the human condition, it can produce work that touches the eternal.

Arrogant Humility The most ridiculous manifestation of spiritual bypassing is performative humility. We can be so proud of being humble that we don’t see our own arrogance. I’ve seen many spiritual seekers cast subtle judgments on anyone they deem “less evolved” while simultaneously insisting they’re beyond judgment. It does not reduce the world’s suffering.

As Watts observes:

“From the standpoint of genuine liberation there are no inferior people. Because the ego never actually exists, those who are most captivated by its illusion are still playing.”

The spiritual ego loves to play the “I’m so enlightened I’m above wanting things” game. But as Watts points out, this creates a paradox:

“All these questions take as real the very illusion which constitutes the actual problem… If the neurotic or ego-ridden individual is one who insists upon being one-up on his own feelings or on life as a whole, the analyst engages him in a game of one-upmanship in which he cannot win.”

The spiritual seeker trying to be “above the ego” is still playing the one-upmanship game, just with more complicated rules. The wise psychoanalyst, or the Zen master, has to play clever tricks to snap the neurotic out of this game.

The Wheel of Samsara is A Playground But there’s another kind of double-bind in spiritual communities: the message that wanting anything makes you unspiritual. This creates people who are secretly ambitious but have to pretend they’re not, leading to all kinds of psychological contortions.

What if instead of trying to transcend your desires, you went fully into them? What if instead of attempting detachment from your goals, you embraced them completely?

Paradoxically, you might discover that full engagement creates less attachment than forced detachment ever could.

The Ice Cream Lesson Looking back, the real teaching that day in Cha-am Thailand wasn’t in any temple or sacred text. It was in watching Vit navigate between worlds, answering my earnest spiritual questions while also being present enough to enjoy ice cream, chuckle at my friends’ jokes about funny-looking depictions of deities, and gracefully navigate the chaotic beauty of coastal Thailand.

He had learned what the hermit Chōmei eventually realized: true freedom isn’t found by rejecting the world but by being with it, without needing to be anywhere other than where you are.

The ice cream melting in my hands was life teaching me about impermanence in the most direct way possible, but I was too busy being “spiritual” to notice at the time.

As Watts writes: “The serious problems of life, however, are never fully solved. If it should for once appear that they are, this is the sign that something has been lost. The meaning and design of a problem seem not to lie in its solution but in our working at it incessantly.”

The aim isn’t to solve the problem of being human. It’s to show up fully for the experience.

Beyond Spiritual Identity Here’s the ultimate spiritual bypassing trap: making enlightenment itself into a goal to achieve rather than recognizing it as the natural state of engaged presence.

Enlightenment, while superb, is the ego’s final disappointment.

Because what the ego discovers is that there was never an ego there to be enlightened in the first place. There was just life, playing itself, and we spent years trying to get “above” the very game we were already playing perfectly.

So maybe the question isn’t “Will you become a monk?” but rather “Will you show up?” Will you engage fully with your ambitions, your creativity, your relationships, your work? Will you stop trying to transcend the human experience and start participating in it?

The most spiritual thing you can do might just be to eat your ice cream before it melts.

This is where the real work begins. Not in achieving a pristine state of transcendence, but in learning to dance fully with whatever life brings, sticky hands and all.

P.S. If this triggered something in you, good. Your ego is realizing its game is up. The question now is: what will you do with that recognition?

Enjoyed This Issue?

Get new issues delivered directly to your inbox, plus exclusive insights on creativity and craftsmanship.